Nutrition, Mental Health, and Education: Supporting Care Experienced Children and Young People

Vanessa and Nicholas Peat

06 June 2025

Children and young people with care experience face a complex mix of unique challenges that can profoundly impact their mental health, wellbeing, and educational outcomes. For the NNECL community, and those working with or caring for these individuals, recognising the role of nutrition as a key pillar of support is essential.

Mental Health Challenges: A Disproportionate Burden

Care-experienced children and adolescents are disproportionately affected by mental health problems compared to their peers. Research shows that 45% of care-experienced children aged 5 to 15 face emotional and mental health issues, compared to just 10% of non-care-experienced children1. For those in residential care, this figure jumps to 72%, highlighting a stark disparity in need2.

Common conditions include:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Chronic stress

These challenges are often rooted in early trauma, instability in care placements, and unresolved emotional struggles.

The Link Between Nutrition and Mental Health

A growing body of evidence supports a strong association between healthy dietary habits and better mental health in children, adolescents, and students in higher education.

Key findings from the latest evidence include:

- Fruit and vegetable intake: Secondary school children who ate five or more portions of fruit and vegetables daily scored nearly four points higher on wellbeing scales than those who ate none. The difference in mental wellbeing between children who consumed the most fruit and vegetables compared with the lowest was of a similar scale to those children experiencing daily, or almost daily, arguing or violence at home (2.95 units lower)3.

- Skipping meals: Children and young people who skipped breakfast or lunch, or substituted breakfast with energy drinks, recorded significantly lower wellbeing scores3.

- Poor dietary habits and Ultra-Processed Foods: High intake of processed snacks, sugary drinks and frequent consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with lower self-concept and increased risk of emotional and behavioural problems4

For university students, the transition to independent living can lead to increased stress and unhealthy eating patterns, such as a higher intake of processed foods and meal skipping, factors that exacerbate fatigue, poor concentration, weakened immunity, mental health struggles and academic challenges. Contributing factors may also include limited access to nutritious food on campus and financial constraints that make healthier choices less attainable5.

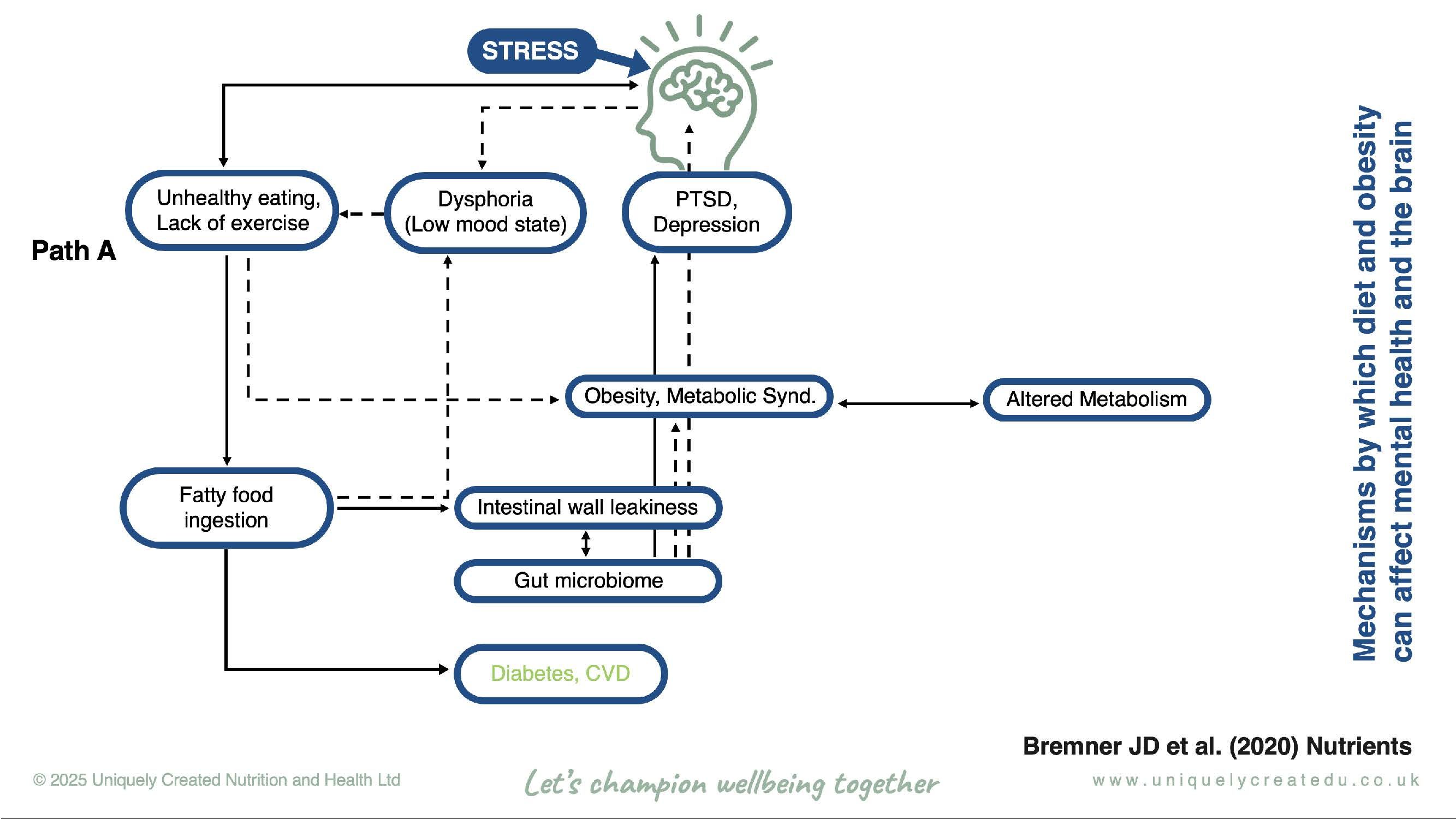

Mechanisms by which diet and obesity can affect mental health

Diet and obesity influence mental health and brain function through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Poor dietary habits, particularly high-sugar and high-fat diets, can trigger inflammation and disrupt insulin sensitivity, which may impair brain regions involved in mood regulation. The gut microbiome, affected by diet, communicates with the brain via the gut-brain axis, influencing neurotransmitter production like serotonin, a key player in emotional well-being. Conversely, chronic stress or mental health disorders can drive unhealthy eating patterns, creating a cyclical relationship between diet and psychological state. Research has found that obesity and metabolic dysfunction may exacerbate these effects by altering brain structure and function, increasing susceptibility to conditions like depression. A balanced diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, appears protective by reducing inflammation and supporting metabolic and cognitive health6.

Figure 1. One of six paths by which stress acts through the brain, affecting eating and exercise behaviours. Dashed lines indicate primary pathways, and solid lines indicate secondary pathways6.

Mealtime Challenges for Care-Experienced Children

Care-experienced children often face specific and frequently misunderstood eating behaviours.

These include:

- Overeating or selective (picky/fussy) eating

- Disordered eating behaviours, such as eating from bins or gorging on food

- Food disgust, pica (eating non-food items), and food-related self-injury (intentionally consuming harmful substances)

These behaviours are often linked to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), food insecurity, and trauma. Care-experienced children are six times more likely to have experienced traumatic events than their non-care-experienced peers, which can shape their food preferences and eating patterns well into adulthood.

Dysregulated and emotional eating patterns are also common in care-experienced children and can be associated with interoceptive difficulties, such as when an individual has problems recognising internal signals like hunger or fullness.

Why Does This Matter?

Extreme eating behaviours are associated with:

- Increased risk of eating disorders

- Poorer mental and physical health

- Lower educational attainment

Foster and adoptive parents often prioritise managing mental health crises and challenging behaviours over creating a positive mealtime environment, due to the adverse day-to-day difficulties they face. Sadly, this creates a vicious cycle, as the latest evidence reveals that children and adolescents with poorer nutritional intake are more prone to engage in violent and dysfunctional behaviour. Furthermore, research shows that traditional dietary interventions do not adequately meet the needs of care-experienced children and their carers. This highlights how critical it is that foster and adoptive parents are provided with the tailored support required for the entire family to thrive and break these vicious cycles.7

Practical, Evidence-Based Strategies to Support Mental Resilience and Emotional Wellbeing

To foster sustainable, positive change, we recommend:

- Consistent, balanced meals: Regular mealtimes built around whole foods - fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins.

- Positive mealtime environments: Calm, non-judgmental settings that support healthy food relationships.

- Address food insecurity: Work with local agencies to ensure reliable access to nutritious food.

- Recognise and respond to trauma: Acknowledge that unusual eating behaviours may be protective coping mechanisms rooted in past trauma.

- Collaborate with nutrition and mental health experts: Seek guidance from professionals to tailor support for care-experienced children.

The Role of Higher Education Institutions and Care Providers

There is a growing call for educational institutions and care providers to:

- Integrate nutritional awareness into mental health education and support strategies, as part of health-related degrees.

- Raise awareness of the connection between diet and emotional wellbeing.

- Offer evidence-based, multi-channel resources provided by nutrition experts accessible to students: online modules, webinars, leaflets, posters, and infographics in dorms, cafeterias, and wellbeing spaces.

- Equip students and care leavers with skills to make informed, sustainable dietary choices to enable them to be proactive in managing their own wellbeing.

Conclusion: Nutrition as a Gateway to Transformation

For care experienced children and young people, nutrition is far more than just fuel, it represents safety, identity, and a sense of wellbeing. These elements are deeply intertwined with emotional resilience and educational success. By recognising their unique challenges and embracing holistic, trauma-informed nutritional approaches, the NNECL community, along with caregivers and educators, can help foster emotional stability, enhance learning outcomes, and empower young people to build healthier lives now and into the future.

Now is the time to turn insight into action. Let’s work together to embed nutrition into our care and education systems, create supportive environments, and ensure every young person has the foundation to thrive now and into their future.

Together, we can make a meaningful difference for those who need it most

References

- NICE. Looked-after children and young people. NICE (2025).

- Smith, N. Neglected Minds. 1–28 (2017).

- Hayhoe, R. et al. Cross-sectional associations of schoolchildren’s fruit and vegetable consumption, and meal choices, with their mental well-being: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Nutr Prev Health 4, 447–462 (2021).

- Zhao, D. et al. Association between dietary habits and emotional and behavioral problems in children: the mediating role of self-concept. Front Nutr 12, 1–11 (2025).

- Solomou, S., Logue, J., Reilly, S. & Perez-Algorta, G. A systematic review of the association of diet quality with the mental health of university students: implications in health education practice. Health Educ Res 38, 28–68 (2023).

- Bremner, J. D. et al. Diet, stress and mental health. Nutrients 12, 1–27 (2020).

- Snuggs, S., Cowan, P., Jethwa, B. & Galloway, E. Eating behaviours in care-experienced children: A mixed-methods UK comparative cohort study to examine mealtime challenges. Appetite 208, (2025).